Family History - Fort Seybert

Seiber Paternal Line Charles & Lydia Seiber Benjamin & Mary Ann Seiber Samuel & Elizabeth Seiber Philip & Catharina Seiber Charles & Rebecca Lones Lones to Seiber Line (Cavett Sta Massacre) James & Harriet Cox

A Variety of Accounts of the Indian Raids on Fort Upper Tract and Fort Seybert - See Additional Maps Below

|

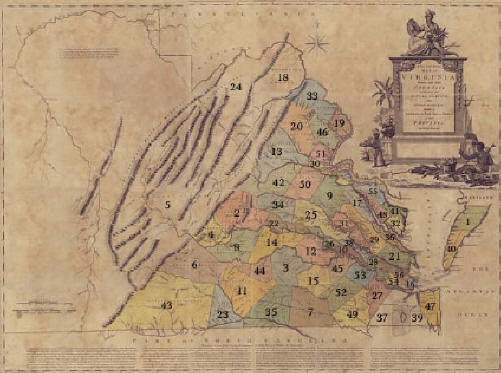

Virginia in 1770 – Augusta County # 5 South Branch of South Fork, Potomac River

From a story which appeared in the Pendleton Times Newspaper.

Western

Virginia was a dangerous place to live at this period, as numerous raids had

been made on the frontiers by the Shawnee Indians under the In January 1756, Col. George Washington recommended to Gov. Dinwiddie that a series of forts be constructed along the mountains, two of them high up on the South Branch. Construction began in August. In March of 1757, Jacob Seybert was commissioned a Captain to head up the militia on the South Branch. On 27 April 1758, the fort at Upper Tract was attacked and 23 people killed. The next day, Fort Seybert was attacked and nearly every adult at the fort was scalped, while the young who were spared were taken captive. Among those killed were Jacob and Elizabeth Seybert and Jacob's mother Hannah Lawrence. The six Seybert children were taken captive. The eldest son, Nicholas, was sold to the French and taken to Canada, where he escaped in 1761. The others were released in 1764.

From A History of Pendleton County, West Virginia by Oren F. Morton, Franklin, West Virginia, February 23, 1910 A most severe blow now befell the west settlements of Pendleton. The defense of Fort Upper Tract was intrusted to Captain James Dunlap who had commanded a detachment in the Big Sandy Expedition. A band of French and Indians appeared in the Valley and on April 27, 1758, they captured and burned the fort, killing twenty-two persons, including Dunlap himself. No circumstantial account of the disaster seems to have been written and we have no assurance that any of the defenders were spared. If the massacre was complete, it would go far to explain the silence of local tradition. So exceedingly little, in fact, has been handed down in this way that some Pendleton people have thrown doubt on the existence of the fort, to say nothing of the burning and killing. There is documentary proof, however, on all these points. The tragedy of Fort Seybert took place on the following day, April 28, 1758. In this case our knowledge is more complete. There were survivors to return from captivity and relate the event. The account they gave us has been kept very much alive by their descendants in the vicinity. Yet these divergences are not very material, although in the course of a century and a half, some variations have crept into the narrative. Through a careful study and comparison of the various sources of information, it is possible to present a fairly complete account of the whole incident. The attacking party was composed of about 40 Shawnees, led by Killbuck. There is a vague statement that a Frenchman was among them. This force was doubtless in contact with the one that wrought the havoc at Upper Tract. But since the recollections of Fort Seybert are nearly silent as to anything that happened at Upper Tract, it is probable that Killbuck took an independent course in returning to the Indian Country. The only mention of Upper Tract in the Fort Seybert narrative is that "an express" was sent there for aid, but turning back after coming within sight of the telltale column of smoke from the burning buildings. The number of persons "Forting" in the Dyer Settlement was, perhaps, forty. Very few of these were men, several having gone across the Shenandoah Mountain the day previous. Some of the women of the settlement appear, also, to have been away. There was a fog shrouding the bottoms of the South Fork on this fateful morning and the immediate presence of the enemy unsuspected. Eastward from the site of the stockade the ground falls rapidly to the level of the river bottom. At the foot of the slope is a damp swale through which was then flowing a stream crossed by a log bridge. A few yards beyond was the spring which supplied water for the fort. A willow cutting was afterwards set near the spring which grew into a tree, four and a half feet in diameter and dried up the fountain. A woman going there for water was unaware, at the time, that an Indian, supposed to be Killbuck himself, was lurking under the bridge. The "brave" did not attempt a capture probably because the bridge was in sight of the Fort and also within easy shooting range. The wife of Peter Hawes, daughter of Roger Dyer, went out with a bound-boy named Wallace to milk some cows. While following the path toward the present post office, they were surprised and captured by two Indians. Mrs. Hawes is said to have had a pair of sheep shears in her hand and to have attempted to stab one of the savages with the ugly weapon. It may have been the same one who had attempted to tease her and whom Mrs. Hawes, collecting all of her strength, pushed over the bank. Reappearing after this unceremonious tumble, the maddened Redskin was about to dispatch her but was prevented by his laughing companion, who called him a "squaw man." Bravery, wherever shown, has always been admired by the American Native. William Dyer, Roger's son, had gone out to hunt and was waylaid near the Fort. His flintlock refused to prime and he fell dead, pierced by several balls from the Indian guns. The presence of the enemy now being known, Nicholas Seybert, a son of the Captain and about 15 years of age, took his station in the upper room of the Fort and mortally wounded an Indian who had raised his head from behind the cover of a rock in the direction of the spring. This seems to be the only loss that the enemy sustained. It is said that a horseman was riding toward the Fort but, hearing the firing and knowing that something was wrong, he hastened to spread the alarm among the more distant settlers. Killbuck called upon the defenders to give up, threatening no mercy if they did not but good treatment if they did. Captain Seybert took the extraordinary course of listening to this deceitful parley. Whether the fewness of adult men or a shortage in supplies and ammunition had anything to do with his resolve is not known. A thoroughly vigorous defense may not have been possible but there was nothing to lose in putting up a bold front. Voluntary surrender to a savage foe is almost unheard of in American Border Warfare. There was the more reason for resisting to the very last extremity, since Killbuck was known to have an unenviable name for treachery in warfare. It is certain that the commander was remonstrated with but, with what looks like a display of German obstinacy, he yielded to the demand of the enemy which included the turning over of what money the defenders possessed. Just before the gate was opened an incident occurred which might have saved the day. Young Seybert had taken aim at Killbuck and was about to fire when the muzzle of his gun was knocked down, the ball only raising the dust at Killbuck's feet. Accounts differ as to whether the aim was frustrated by the boy's father or by a man named Robertson. Finding the surrender determined upon, the boy was so enraged that he attempted to use violence upon his parent. He did not, himself, surrender but was taken prisoner by being overpowered by the savages. As the Indians rushed through the gate, Killbuck dealt the Captain a blow with the pipe end of this tomahawk, knocking out several teeth. After the inmates were secured and led outside, the fort was set on fire. A woman named Hannah Hinkle, perhaps bedfast at the time, perished in the flames. Taking advantage of the confusion of the moment, the man Robertson managed to secrete himself and, as the savages withdrew, he hurried toward the river, followed a shelving bluff so that his footsteps might the less easily be traced, and made his way across the Shenandoah Mountain. He was the only person to effect his escape. The captives appear to have been halted on a hillside about a quarter of a mile to the west. Here, after some deliberation on the part of the victors, they were gradually separated into two rows and seated on logs. One row was for captivity and the other for slaughter. On a signal the doomed persons were swiftly tomahawked and their scalped and bleeding bodies left where they fell. Mrs. Hawes fainted when she saw her father sink under the blows of his executioner and to this circumstance she may have been indebted for her exemption. James Dyer, a tall, athletic boy of fourteen years broke away and, being a good runner, attempted to reach a tangled thicket on the river bank a half mile eastward and the same distance above the present post office. He almost succeeded in reaching and crossing the river but was finally headed off and retaken. It was now probably past noon and the Indians, with their convoy of eleven captives and their own wounded comrade, borne on an improvised litter, began the climbing of South Fork Mountain. A woman whose given name was Hannah had a squalling baby. An Indian seized the infant and stuck its neck in the fork of a dogwood. The mother found some consolation in the belief that her child was killed by the blow and not left to a lingering death. Greenwalt Gap, nine miles distant was reached by nightfall by taking an almost air line course regardless of the nature of the ground. Here the disabled Indian died, after suffering intensely from a wound in the head. He was buried in a cavern 500 feet up the mountain side. Until about sixty years ago portions of the skeleton were still to be seen. The next halt was near the mouth of the Seneca and without pursuit or mishap, the raiding party returned to its village near Chillicothe, Ohio. The people slain in the massacre were seventeen, some accounts putting the number at twenty-one or even more. Among them were Captain Seybert, Roger Dyer and the bound boy Wallace, whose yellow scalp was afterwards recognized by Mrs. Hawes. It is the brunette captive that Indians have preferred to spare. Including William Dyer, the four names are the only ones remembered. It is worthy of note that apart from Seybert and the two Dyers, none of the heads of families in the region around appear to be missing. Possible exceptions are John Smith, William Havener and William Stephenson. The infant son of William Dyer was with his mother's people east of Shenandoah Mountain. Of the captives the only remembered names are those of Nicholas Seybert, James Dyer, the wives of Peter Hawes and Jacob Peterson and a Havener girl {NOTE: John Jacob Seybert had a sister Elizabeth who married a Nicholas Havener}. The girl either escaped or was returned and counseled settlers to be more careful in the future in exposing themselves to the risk of capture. A brave took pity on Mrs. Peterson and gave her a pair of moccasins to enable her to travel with greater comfort. It is not remembered whether any of the captives returned, except the two boys mentioned, Seybert and Dyer and the Havener girl. As the party was about to cross the Ohio, young Seybert remarked upon a flock of wild turkeys flying high in the distance. "You have sharp eyes," observed Killbuck. "Was it not you that killed our warrior?" "Yes, and I would have shot you, too, if my gun had not been knocked down." "You little devil," commented the chief, "if you had killed me my warriors would have given up and come away. Brave boy! You'll make a good warrior. But don't tell my people what you did." Several years after his return the young man sold his father's farm to John Blizzard and he made a new home on Straight Creek. Some of his descendants still live in the vicinity. James Dyer was among the Indians for about two years. He sometimes accompanied a trading party on a visit to Fort Pitt, now Pittsburgh. On his last trip he resolved to attempt to escape. He eluded the Indians and slipped into a cabin of a trader and the woman within hid the boy behind a large closet and chest, piling over him a mass of furs. In trying to find him the Indians came into the hut and threw off the skins, one by one until he could see the light through the opening among them but fortunately, for his purposes, the Indians thought it not worth while to make the search complete. After remaining a while at the old home in Philadelphia, the young man returned to Fort Seybert and for more than forty years was one of the most prominent citizens of the county. James Dyer is said to have been instrumental in effecting the rescue of his sister Sarah Hawes by her brother-in-law, Matthew Patton. Her captivity lasted three and a half years. A complete account of this tragedy may be found in a pamphlet by Mary Lee Keister Talbot entitled ""The Dyer Settlement and the Fort Seybert Massacre." The following version of the rescue of Mrs. Hawes is given in an article by Mrs. Alonzo D. Lough, in "The Moorefield Examiner" of Moorefield, West Virginia. When Matthew Patton took his cattle to market at Pittsburgh, the dealer to whom he sold them told him an Indian tribe there had a "red headed woman" among them. Mr. Patton suspected that this was his wife's sister and had the dealer to arrange for her to come into his store, where he concealed her behind his counter, and covered her with furs. The Indians began to search for her and entered the store, and as in searching for her brother, threw off part of the covering hides. Thoroughness not being characteristic of Indian habits, they ceased in both searches, before uncovering the fugitives. That night Mr. Patton accompanied by Mrs. Hawes, left Pittsburgh secretly and traveled until daylight when he hid her in the top of a fallen tree. Night came on and Mr. Patton rejoined her and they traveled again. After that he provided her with other clothes instead of her Indian apparel and they traveled by day until their return. Mrs. Hawes had been with the Indians seven years and had traveled to the Great Lakes and over much of the prairie of the middle west. The sale of personal property of James Dyer in 1807, netted $1975. Inventory included 8 horses, 65 cattle, 62 hogs and 23 sheep. There were 15 books, a Bible going for $9 and a copy of Johnson's Dictionary at $3.33. The furnishings of the house amounted to $189, including a clock selling for $60 and a desk at $25. We here have a man who read books, was considered rich and owned the best furnished dwelling in the county. Roger's estate, in 1810, brought $6403.33.

From The Dyer Settlement, The Fort Seybert Massacre by Mary Lee Keister Talbot, A.B., Hollins College, M.A., University of Wisconsin. The morning of the 28th of April (1758) dawned upon Fort Seybert with a fog hanging over the valley of the South Fork, as if presaging the calamity that hung over the heads of the settlers. By an unfortunate conjunction of events, a part of the men were absent from the settlement, having crossed the Shenandoah mountain the day before. Probably because of their absence, the remaining men and the women and children were gathered within the fort. They knew that danger was imminent but unaware of the immediate presence of an enemy, while stealing stealthily upon them, concealed by the fog, and protected by the forest, was a party of forty Shawnee warriors. They were not the band that had wrought the destruction at Upper Tract the day before, nor did they join them on their return. These had come from beyond the Ohio River, had crossed the Alleghenies and now descended upon the South Fork Valley as their field for desolation. At their head was the treacherous and revengeful Killbuck. It is probable that, according to the usual Indian plan in attacking a settlement, they had separated into several groups for the purpose of surprising and capturing the scattered settlers providing they were not all in the fort. One of these parties captured Mrs. Henry Hawes (Sarah Dyer Hawes, daughter of Roger and Hannah Dyer, widow of Henry Hawes at this time) at her home on what is now the Laban Davis place near Brandywine, opposite the mouth of Hawes' Run. She was taken on down the river toward the fort and as her captors conducted ther along the high bank of the river above the present residence of A. D. Lough, she suddenly pushed the one (Indian) next (to) the river over the bank. He returned in a rage, threatening to kill her, but his companions restrained him and laughed at him, calling him a squaw man ....... "The first violent act of the savages near the fort was the killing of William Dyer (son of Roger and Hannah Dyer and Mrs Hawes' brother). Mr Dyer was out hunting when waylaid by the savages. He attempted to fire upon them but his flint lock missed fire and they shot him dead. It transpired afterward that an Indian, probably Killbuck, had been secreted under the bridge leading across a ravine to the spring when one of the women had crossed in the morning for water. He permitted her to cross and return unmolested. "There is a tradition that a solitary horseman was riding toward the fort in the early morning, and, hearing the sound of firing and suspecting there was an Indian attack, hastened away to give the alarm to distant settlers. Also that a messenger was secretly dispatched to Fort Upper Tract for aid, but when he came in view of the fort the smouldering ruins met his astonished gaze. There is also a doubtful tradition that a Frenchman was among the attacking party at Fort Seybert. Now that the presence of the foe was known, the settlers fastened the gate and put themselves on the defensive. An Indian peering up over the ledge of rocks under the brow of the hill eastward was espied by Nicholas, fifteen-year-old son of Capt. Seybert, from his position at a loophole, and fired upon. His head instantly disappeared and young Seybert soon saw feathers floating upon the stream below, from which he judged his bullet had hit its mark and cut loose the savage's head-gear. "Killbuck now changed from attack to strategy and called out to Capt. Seybert in English that if they would surrender they would all be spared, but if not they would all be killed. Seybert entered into a parley with Killbuck, as a result of which he agreed to surrender without further resistance and turn over to the Indians the money and valuables in the fort. Killbuck agreed that the inmates of the fort should not be harmed. Some of the settlers favored this conditional surrender while others opposed it. Nicholas Seybert was bitter in his opposition and attempted by violence to prevent his father from making the surrender. Before the gate was thrown open he took aim at Killbuck and would have shot him dead but that his gun was knocked aside by his father. The bullet struck at Killbuck's feet. ..Killbuck greeted Seybert by striking him in the mouth with the pipe end of his tomahawk, knocking loose his front teeth. This deed and the action of the savages showed the settlers too late what they might expect, and confusion followed. Young Seybert refused to surrender and was overpowered. A man named Robertson managed to secrete himself and was the only one to escape. "The inmates were made prisoners, the money and valuables secured and the block house set on fire. A woman named Hannah Hinkle who was probably bedfast perished in the flames. The man Robertson escaped from the stockade, made his way unnoticed down the eastern bluff, followed the shelving rocks to the river, crossed over and fled across Shenandoah Mountain. The Indians took their prisoners up the slope toward the South Fork mountain about a quarter of a mile. Here they divided them into two groups, placing in one group those whom they selected as desirable for captives. Nothing of mercy or humanity entered into their choice, only expediency from the Indian point of view. The object of the Indian in preserving captives was to adopt them and thereby strengthen his tribe. He wanted brave young men who would make valiant warriors. He wanted no old people, no weaklings, no cowards. He preferred brunettes to blondes because they resembled his swarthy complexion more nearly. The fact that most of the captives preserved in Indian raids endured the hardships and privations to which they were subjected shows that the selections for physical fitness were well made. At some point of time while the prisoners were being separated, James Dyer, a fleet footed youth of fourteen, broke from among them and attempted escape by flight. So swift was he that his eager pursuers did not overtake him until he had reached the river about three quarters of a mile distant. Here in a cane brake, opposite the present dwelling of J. W. Conrad, he was overtaken. Because of his swiftness he was preserved.

From account by Andrea Dalen Larrivee, Descendant of early settler, Roger Dyer Roger Dyer was a middle-aged man when he moved with his wife, Hannah, and five children from Lancaster County, PA to the Moorefield area. He and his son, William, purchased 1,160 acres on the South Fork of the South Branch of the Potomac River in 1747. The family moved onto the land in 1748 and were some of the first permanent settlers in the area. His three daughters, Hannah, Hester and Sarah, subsequently married men who owned or bought adjacent property. By the year 1758, four of Roger Dyer's children were married, and he had seven grandchildren. They were prosperous by the standards of the day, but life would have been quite difficult as their land was on the westernmost edge of the settled colonies. Native American tribes wandered freely in the area, hunting and trading. The settlers had to make a long, arduous journey over the Shenandoah to get to their markets and seat of government. The settlers' relations with the Indians who used this area were fairly cordial until about 1754. The French and Indian War had begun in 1753, and the Shawnee, one of the primary tribes in the area, were influenced by their Ohio kinsmen to be loyal to the French cause. This was understandable. The French used the areas they controlled in a way that didn't threaten the Indian way of life. They hunted and trapped, traded with the natives and often took Indian wives. The English, however, were true settlers. They bought the land, cleared and fenced it, built homes and settlements, and drove the game and the Indians farther west. Because of Indian raids in areas to the northwest, George Washington ordered that two forts be built on the upper South Branch. Fort Upper Tract and Fort Seybert were built in 1757. Fort Seybert (named for Jacob Seybert, who had moved to the area in 1753 and had been commissioned in 1757 as the first captain of militia in that section) was close to the Dyer family settlement. On April 27, 1758, many of the men and probably some of the women and children from the area left for a journey over the Shenandoah Mountain. The people who remained were staying at the fort, probably due to their vulnerability. They were no doubt aware of troubles in other areas with Indians who were sometimes accompanied by French. The morning of April 28 was foggy. Sarah Dyer Hawes, who had been widowed for about three years, and a boy named Wallace, who may have been an indentured servant, were outside the fort on their way to milk or to shear some sheep. Two Shawnee braves accosted them. Sarah attempted to stab one of the men with her sheep shears. During the scuffle Sarah pushed the brave over an embankment. The remaining Indian found the situation very funny, and in the midst of the laughter, Sarah and Wallace returned to the fort. William Dyer went out on that same morning to hunt. Not far from the fort, he was shot by the Shawnee and became the first casualty of that day. Nicholas Seybert, son of Jacob, heard the shots and fired at the Indians, hitting one brave who was the only Indian casualty. Killbuck, the Shawnee chief who was leading this group, spoke English and decided to negotiate with the settlers. He proposed to the settlers that they surrender. He guaranteed that there would be no blood shed and that, as his captives, the settlers would be well treated. Otherwise, everyone would be killed. Jacob Seybert, speaking for the settlers, agreed to Killbuck's proposal despite some dissension, notably by his son, Nicholas. Nicholas tried to shoot Killbuck, but his father disrupted his aim and the ball landed at Killbuck's feet. If the shot had met its mark, the events of the day may have been very different. Contrary to his word, Killbuck and his warriors moved the settlers to an area uphill from the fort where they were separated into two groups: those who would live as captives and those who would die. Among those who were to die were Sarah Dyer Hawes, James Dyer and Roger Dyer. Sarah saw her father hit in the mouth by a tomahawk, knocking out some of his teeth, and she fainted. This may have saved her life. For whatever reason, she was spared. James Dyer, who was 14 years old, managed to escape and tried to outrun his captors. Although he was recaptured, the Indians were impressed by his athletic prowess and spared his life as well. The doomed prisoners were made to sit on a log. An Indian stood behind each person, and on a command from Killbuck, the prisoners were murdered and scalped. Sarah and James along with nine other captives were forced to accompany the Shawnee, leaving 17 dead behind. They walked over the South Fork Mountain on that day. Along the way an infant who was crying was killed and left hanging in the forked branched of a dogwood tree. Their first night was spent at Greenawalt Gap near present day Kline. The second night was spent at Seneca. From there they journeyed to a Shawnee village near what is now Chilecothe, OH. James remained in captivity for two years. During that time he was often pitted against new captives in foot races called "running the gauntlet." Two racers would run between lines of Indians who hit them with sticks and whooped loudly in an effort to make the racers run more swiftly. The loser of the race was often killed. For the most part, however, the Shawnee treated their captives relatively well. The purpose of keeping captives was not to have slave labor but to acquire new tribe members, so the captives were encouraged to integrate into Indian life. James became a trusted tribe member and was allowed to hunt and go on trading trips. On one such trip to Fort Duquesne (present day Pittsburgh, PA), he managed to allude his captors and slip into a cabin. A woman inside hid him under a pile of furs. The Shawnee searched for him, removing some of the furs as they looked through the cabin, but James wasn't discovered. He made his way to Lancaster County, PA, where he spent some time with family friends. Eventually he returned to the Fort Seybert area. Sarah was a captive for a longer time, probably about five years. James rescued her some years after he had made his escape. He returned to Ohio and found the camp where Sarah was. Hiding near a spring, he made contact with Sarah when she came to get water. They made arrangements to escape that night. Sarah gathered her few belongings, among them a spoon made of buffalo horn, which is still owned by her descendants. She and James rode away on horses James had brought, and they returned to the South Branch. Sarah had a daughter, Hannah, who was only two or three years old when her mother was captured. When Sarah returned, Hannah was terrified of her because of her Indian dress and mannerisms and her tanned skin. James and Sarah continued to live in what is now Pendleton County. Sarah married Robert Davis, had seven more children and lived on a farm near Brandywine, which is still owned by their descendants. James married three times and had a total of 16 children. The above story was written by Andrea Dalen Larrivee, g,g,g,g,great granddaughter of Roger Dyer.

Other Facts:

Mary Elizabeth Theiss

and Jacob Seibert (Seybert) were married on Febuary 26, 1739, in

Tulpehocken, Pennsylvania, by the Rev. John Casper Stoever. They received a

tract of land in Bethel Township that year and stayed there until 1749 when

they sold their100 acres and went to the South Branch of the Potomac in

Augusta Co., VA. Jacob appears on the Augusta Co. delinquent tax list that

year. On May 21, 1755, Jacob Seybert was deeded a 210 acre tract of land

from Robert Green. It adjoined the land of Nicholas Heavener, who was

married to Jacob's sister Elizabeth. From Annals of Bath County, Virginia:

James Samuel Curry

married Mollie J. Harman on October 6, 1880. Mollie was the daughter of

George and Susan (Smit)h Harman, both born in Pendleton County, West

Virginia. Her great-great-grandfather was the Captain Robert Davis who led

the whites in pursuit of the Indians after the massacre of Fort Sibert. Mary

Dyer, then twelve years of age, was among those made captive, and she

remained with the Indians three years. On her return she became the wife of

Captain Davis, and she was the great-great-grandmother of Mrs. James Samuel

Curry. |

| Fort Seybert is near the juncture of

present-day Augusta County, Virginia, and Pendleton County, West Virginia.

|